Asabiya: A Concept We Need to Revive in 2025

A 14th century Arab thinker developed a theory about group cooperation and identity in the face of an external threat, which we need to revisit in the Trump era

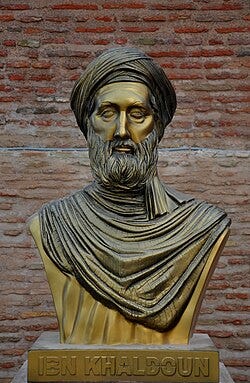

Bust of Ibn Khaldoun in the entrance of the Kasbah of Bejaia, Algeria. © Reda Kerbouche, CC-BY-SA, GNU Free Documentation License, Wikimedia Commons

In 1952, Dwight Eisenhower, the former Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, entered the Presidential race of the United States (US) as a Republican. His mission was to stop Robert A. Taft, an isolationist Senator. He won the primary and the subsequent election; and spent much of his eight years in office trying to contain communism.

In 1987, another Republican President, Ronald Reagan gave a famous speech in Berlin, with a clear message to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev: “Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” A little over two years later, the communist government of East Germany announced that citizens could visit West Berlin. Crowds tore down the wall. The Soviet Union, which had conquered East Germany at the end of World War II, entered the history books two years later.

Let’s fast-forward to 2025. Another Republican, Donald Trump, is in the White House. He has threatened to withdraw military aid to Ukraine, said that the country cannot win its war with Russia, and has accepted the narrative of the invaders. In February, his Vice President, JD Vance, gave a controversial speech in Munich, Germany, accusing European countries of backsliding as democracies. In March, Vance told his colleagues in a supposedly secret chat about bombing Yemen: "I just hate bailing Europe out again." He later visited Greenland to support his boss’ territorial claims.

Clearly, something significant has changed on the US right in the 38 years between 1987 and 2025. Perhaps surprisingly, the change in strategy and tone would have been foreseeable to the great Arabic thinker Ibn Khaldun (1332 to 1406), a contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer in the West. In the 14th century, Khaldun developed the concept of asabiya (or asabiyya). It can be defined as group cooperation and integration in the face of an external threat.

Our guide will be Peter Turchin, a Russian-American complexity scientist, who wrote a book on the idea in 2007, which is well worth revisiting in 2025.

Asabiya refers to the capacity of a social group for concerted collective action. Asabiya is a dynamic quantity; it can increase or decrease with time. Like many theoretical constructs, such as force in Newtonian physics, the capacity for collective action cannot be observed directly, but it can be measured from observable consequences.

Khaldun used asabiya as a way of analysing the rise and fall of empires.

Expansionist empires exert enormous military pressure on the peoples beyond their boundaries. However, the frontier populations are also attracted to the imperial wealth, which they attempt to obtain by trading or raiding. Both the external threat and the prospect of gain are powerful integrative forces that nurture asabiya. In the pressure cooker of a metaethnic frontier, poorly integrated groups crumble and disappear, whereas groups based on strong cooperation thrive and expand.

To match the power of the old empire, a frontier group with high asabiya — an incipient imperial nation — needs to expand by incorporating other groups. On a metaethnic frontier, integration of ethnically similar groups on the same side of the fault line is made easier by the presence of a very different “other” — the metaethnic community on the other side. The huge cultural gap across the frontier dwarfs the relatively minor differences between ethnic groups on the same side.

Ibn Khaldun saw history as being somewhat cyclical.

The very stability and internal peace that strong empires impose contain within them the seeds of future chaos. Stability and internal peace bring prosperity, and prosperity causes population increase. Demographic growth leads to overpopulation, overpopulation causes lower wages, higher land rents, and falling per capita incomes for the commoners. At first, low wages and high rents bring unparalleled wealth to the upper classes, but as their numbers and appetites grow, they also begin to suffer from falling incomes. Declining standards of life breed discontent and strife. The elites turn to the state for employment and additional income, and drive up expenditures at the same time the tax revenues decline because of the growing misery of the population. When the state’s finances collapse, it loses the control of the army and police. Freed from all restraints, strife among the elites escalates into civil war, while the discontent among the poor explodes into popular rebellions.

There are, of course, significant differences between the contemporary world and Khaldun’s world. True empires are far less common nowadays, with the exception of Vladimir Putin’s Russia; populations in the developed world are falling rather than growing; and tech has been keeping societal collapse at bay since the industrial revolution. Even so, Khaldun’s central point really does stand: populations do tend to unite in the face of an external threat and turn on themselves in peacetime.

Asabiya explains what has happened to the American right. Soviet-led communism provided a clear external enemy for decades up to the 1990s. From the start of the Cold War, anti-communists from the US were able to find common ground with the American centre-left, as well as with allies from Europe, Japan and South Korea, in the face of the threat. Deterrence was a sensible strategy in the face of Soviet expansionism.

It might be a hard lesson for some, but the American right was absolutely correct on one central point during these decades: market-based economies with lots of failed projects really do work better than planned economies with no margin for error. If in doubt, please consult the twin studies in Germany and Korea, which made the point loudly and clearly.

It should go without saying that the point of this essay is not to whitewash every decision taken by the American right up to the 1990s. It should be obvious that Senator Joe McCarthy’s witch-hunt against sympathisers of communism or socialism; the Vietnam war; and the coup to topple Salvador Allende in Chile were all terrible mistakes, which all pushed in a similar direction - over-reaching in the fight against communism while also undermining the democratic values that were supposedly being defended at home.

Without an external enemy, asabiya in the US has fallen sharply since the 1990s. The result - a fierce and divisive culture war - would have been obvious to Khaldun. The 14th century Arab intellectual would probably also have winced at Trump and Vance’s threats to take over Greenland (an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark), undermine the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and impose punitive tariffs on allies and trading partners. Long Europe’s security guarantor, the US is increasingly acting as an external threat to the Old Continent. What could possibly go wrong?

A close reading of the news show us that asabiya is soaring throughout Europe in response to the new American threat and Putin’s aggression. For example, more than half of Europeans see Trump as an “enemy,” according to a recent poll. Meanwhile, the French are talking about developing a shield of European nuclear weapons.

Trump’s aggressive stance has created a problem for European hard-right parties that share his culture-war instincts. Should they double down on the fight against “wokeness” or should they distance themselves from the American leader, who is seen as increasingly toxic by their potential voters? Italian Prime Minister (PM) Giorgia Meloni highlighted the dilemma in her first interview with a foreign newspaper in March (paywalled): she said that Europe should resist a “superficial” or “childish” analysis that paints Trump as a threat. Good luck with that!

If Trump’s administration continues to act as an external threat to Europe and Canada, we can expect asabiya to go through the roof. Previous minor differences will seem increasingly unimportant; and people will develop more expansive identities. Expect increasing cooperation between Canada and Europe, for example.

We have said before that “nationalism means war.” A contemporary take on Khaldun can also turn this around: the threat of war can lead to new national identities. The rise of European nationalism would also be a good bet. People like me, who emphasise moderation and criticise the toxic excesses of nationalism, can only hope that if we see this new ideology, it will be civic nationalism (based on shared values and institutions) rather than ethnic nationalism (based on heritage).

There is also an alternative scenario, which Spanish PM Pedro Sánchez hinted at in March (paywalled). The country is a laggard when it comes increasing NATO spending. Sánchez has been having difficulties agreeing a budget for 2025 with his hard-left allies. He said that there is no threat of Russia “bringing its troops across the Pyrenees.” He has been arguing that cybersecurity should be included in rising defence budgets.

Sánchez’s lukewarm response to Putin’s threat and Trump’s new stance show that asabiya might be unevenly distributed. We can expect a North/South divide. A certain amount of unity for the countries around the Baltic Sea might make more sense than pan-European identities. Putin’s external threat certainly looks different in Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Sweden than it does in Spain or in Italy.

By Gabriel Ziegler - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=125638072

In this context, it will be very interesting to keep an eye on Russia’s Kalingrad Oblost, which is cut off from the rest of its territory, but sits among the Baltic states. The Oblost’s independence movement was banned in 2003. Increasing asabiya around the Baltic and Nordic region could yield unexpected results. I will refrain from making any specific predictions. The comments are open. See you next week!

Previously on Sharpen Your Axe

The many failures of communism

Further Reading

War and Peace and War: The Rise and Fall of Empires by Peter Turchin

This essay is released with a CC BY-NY-ND license. Please link to sharpenyouraxe.substack.com if you re-use this material.

Sharpen Your Axe is a project to develop a community who want to think critically about the media, conspiracy theories and current affairs without getting conned by gurus selling fringe views. Please subscribe to get this content in your inbox every week. Shares on social media are appreciated!

If this is the first post you have seen, I recommend starting with the fourth-anniversary post. You can also find an ultra-cheap Kindle book here. If you want to read the book on your phone, tablet or computer, you can download the Kindle software for Android, Apple or Windows for free.

Opinions expressed on Substack and Substack Notes, as well as on Bluesky and Mastodon are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.

Excellent piece, very apt, but I think you're being a bit harsh on Sanchez. He's playing the hand he's been dealt and getting any kind of increase in defence spending is a significant start. It's inevitably going to be seen as less important an issue than in some other countries but Sanchez is very pro-European; if it were up to him alone, I suspect he'd go much further but the political realities are the political realities.