Cooperative Apes

What can we learn about our species from a new generation of researchers who are seeking to ground the social sciences in evolutionary theory?

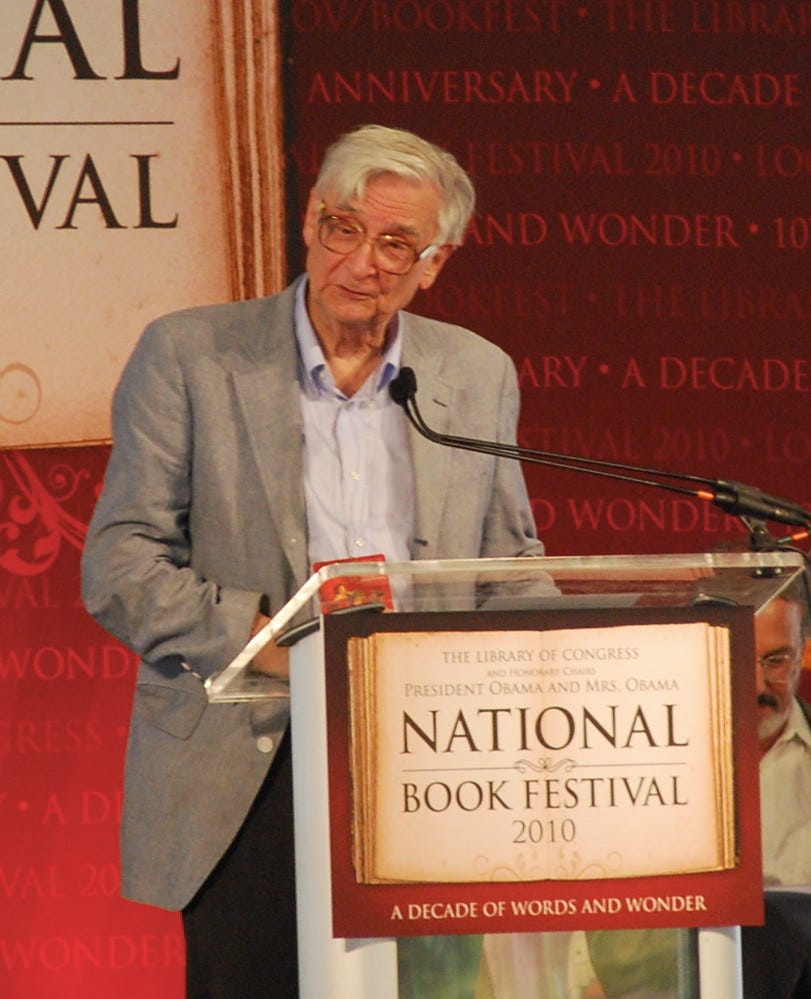

"E.O. Wilson 1" by afagen is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

American entomologist E. O. Wilson drew rather hysterical criticism in the mid-1970s when he suggested that natural selection might have influenced human behaviour. He made the modest suggestion that social scientists should maybe include biologists in the conversation; and was smeared as a fascist and a racist as a result.

Protesters who tried to smash up one of Wilson’s talks chanted: “Racist Wilson, you can’t hide, we charge you with genocide.” However, Steven Pinker, a psychologist, says that few of Wilson’s critics actually seemed to have read the controversial chapter of his 1975 book where he made the explosive suggestion, let alone understood it. Some of his critics smeared him as a “right-wing prophet of patriarchy,” while he was actually a lifelong liberal Democrat, who argued that human populations are extremely similar on a genetic basis.

By the late 1980s, Wilson’s proposed new field of sociobiology had largely been discredited in respectable circles, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt said. However, that did not mean the biologist’s insight was wrong. A few researchers quietly mined evolutionary theory for insights into human nature away from the spotlight. By 1992, sociobiology had been reborn as evolutionary psychology; and significant insights into human nature began to emerge in the following years.

By the time Wilson wrote an update to his 1975 book in a new work called Consilience in 2014, he was able to say that the challenge of understanding altruism in humans and animals - the central problem he had proposed was how members of the ape family can learn to cooperate - had “largely been met” in the intervening years, despite the initial hostility of his critics.

Almost 50 years later, it is a little difficult for us to understand why Wilson’s original suggestion was quite so controversial. Pinker gives us some context:

In the 1970s, many intellectuals had become political radicals. Marxism was correct, liberalism was for wimps, and [Karl] Marx had pronounced that “the ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class.” The traditional misgivings about human nature [in the social sciences] were folded into a hard-left ideology, and scientists who examined the human mind in a biological context were now considered tools of a reactionary establishment.

Wilson himself was an expert in ants, which have evolved to be naturally highly cooperative, unlike great apes like ourselves. In 1994, he icily dismissed Marxism in four words: “Good ideology. Wrong species.” In the same year, he made a similar comment in a slightly different form: “It would appear that socialism really works under some circumstances. Karl Marx just had the wrong species.”

It is easy to see why Marxist social scientists in the 1970s might have had such a hostile reaction to an approach that seemed to bring critical scrutiny to the very basis of their ideology, particularly given the failure of social Darwinism to provide good results for society. Unfortunately for the theorists, within a decade and half, Marx’s failure to make correct predictions was exposed to the world with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of serious attempts to make communism work.

Social theorists’ attempts to maintain their status with post-Marxist speculation have been unimpressive since then, to put it as politely as possible. Evolutionary psychologists have done a much better job when it comes to connecting their ideas to the world outside our heads.

What is the problem of altruism that Wilson referred to? An evolutionary psychologist called Nichola Raihani does a great job of explaining the issue in a book published in 2021. “Cooperation is our species’ superpower, the reason that humans managed not just to survive but to thrive in almost every habitat on Earth,” she writes.

As Wilson noted, ants are also highly cooperative. However, Raihani says that ant colonies can be conceived of as “super-organisms,” with the interests of members permanently aligned so individuals can safely surrender autonomy. With humans, though, our interests can sometimes converge, leading to competition within a group. This can result in the prisoner’s dilemma, when we have to decide whether to collaborate with someone else or to betray a would-be ally. The choice of whether to collaborate or whether to defect is rarely set in stone.

Despite the difficulties, human cooperation has deep roots. It also makes us very different from our cousins in the ape family, Raihani says.

Many primates live in social groups, and humans are no exception. Nevertheless, we are unique among the great apes in that we also live in stable family groups, where mothers receive assistance from others in the production of young. The evolution of our family - fathers, siblings and grandparents - was the first critical step on our path towards becoming a hyper-cooperative species.

Raihani argues that our species is very egalitarian compared to our cousins when it comes to reproductive success. Among hierarchical great apes, like gorillas, alpha males sire nearly all a group’s offspring. By contrast, reproduction tends to be shared much more equally among human males, even in contemporary hunter-gatherer societies. “Countless anthropological reports detail how men who throw their weight around, or try to monopolise women or resources in the group, can expect to be ostracised, excluded from the group, or even killed.”

Although human leadership probably started out as inclusive and democratic, there was probably a significant change with the agricultural revolution, Raihani argues. Over many generations, leaders of farming societies gradually became increasingly despotic. Estimates suggest around one man in three sired offspring just before humans left Africa. This seems to have dropped to around 16 childless men for every one who reproduced by the time farming had gained traction.

Kings fathered hundreds of children, while many ordinary men died in warfare or in rituals or became slaves or eunuchs. On the other side of the coin, monogamy has become the norm in many human societies since the birth of despotism in early farming societies.

The best way of thinking about these issues is to see human nature as a tug of war between the individual urge to dominate others and the collective interest of the group in not being dominated, Raihani says. Every society finds its own balance between the two poles, for a time, but the tension can never be fully resolved.

Although cooperation tends to be positive, it also has its darker side. It frequently has victims. Raihani urges us to think of “corruption, bribery and nepotism” as forms of cooperation that pass the costs onto others in society. On the other hand, though, the state’s ability to offer material security means that “the boundaries of our social circles can relax a little, expanding to include people from beyond the core network of family and close friends.” This can facilitate liberal democratic institutions.

Last week’s essay on finance mentioned biologist, psychologist and economist Joseph Henrich’s work on the evolution social norms. It is time to take a deeper dive into his book on the subject, which was published in 2015. He begins with a contrast between Sir John Frankin’s 1845 search for the Northwest Passage between Europe and Asia in the Arctic and a lone native woman who survived by herself for 18 years from 1830 on San Nicolas Island in the Pacific.

Franklin’s ship was trapped in ice for longer than he expected. He died. His crew fragmented. Lacking the tools or the knowledge they needed to survive in this harsh environment, where natives had lived for centuries, they resorted to cannibalism.

Meanwhile, the native woman who survived by herself on San Nicolas Island was just fine after fashioning bone knives, needles and fishhooks while living in a whalebone house. She even offered her rescuers a home-cooked meal when they finally arrived. Why were the outcomes of both groups so different?

Our species’ uniqueness, and thus our ecological dominance, arises from the manner in which cultural evolution, often operating over centuries or millennia, can assemble cultural adaptions. In the cases above, I’ve emphasized those cultural adaptions that involve tools and know-how about finding and processing food, locating water, cooking, and traveling. But as we go along, it will become clear that cultural adaptions also involve how we think and what we like, as well as what we can make.

The people who accused Wilson of fascism are probably feeling very uncomfortable now. However, Henrich is careful to stress that his book is “not about the genetic differences among current populations in our species now.” He says that racial categories developed by 19th century Europeans contain “little, if any, useful genetic information, aside from capturing something of the migration patterns of ancient peoples.” He stresses the need for more evolution-grounded research, not less.

The most interesting section of Henrich’s book talks about the way we have “an instinct to faithfully copy complex procedures, practices, beliefs, and motivations, including steps that may appear causally irrelevant, because cultural evolution has proved itself capable of constructing intricate and subtle cultural packages that are far better than we could individually construct in one lifetime.” We are primed to copy others, particularly those of the same gender, who we are older than us and perceived to be successful - a big secret of Donald Trump’s success with a certain class of male voters in the US after playing a successful businessman on television for so long.

What can we learn from the researchers like Raihaini and Henrich, who took Wilson’s suggestion in the 1970s to ground social theory in biology and then ran with it? Two obvious conclusions are that as our oldest institution, we should support the family wherever possible; and as primates with an instinct to copy and learn, we should place the education system at the heart and soul of the welfare state. The comments are open. See you next week!

Previously on Sharpen Your Axe

Troubling maths for people who believe in deep genetic differences between populations

The fundamental unity of humanity

Power corrupts and the power of negative thinking

My personal reaction to the fall of the Berlin Wall

The predictive failures of Marxism

There is a world outside our heads

We should strive to separate our values and our worldview

Institutionalism and the peaceful transition of power

Last week’s essay on social norms in finance

Chesterton’s fence helps us appreciate hard-to-understand institutions

Haidt’s work on motivated reasoning; his insight that we are 90% chimp and 10% bee; and his work on the moral intuitions at the base of our worldviews

Further Reading

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt

The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter by Joseph Henrich

The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature by Steven Pinker

The Social Instinct: How Cooperation Shaped the World by Nichola Raihani

Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge by E. O. Wilson

This essay is released with a CC BY-NY-ND license. Please link to sharpenyouraxe.substack.com if you re-use this material.

Sharpen Your Axe is a project to develop a community who want to think critically about the media, conspiracy theories and current affairs without getting conned by gurus selling fringe views. Please subscribe to get this content in your inbox every week. Shares on social media are appreciated!

If this is the first post you have seen, I recommend starting with the third anniversary post. You can also find an ultra-cheap Kindle book here. If you want to read the book on your phone, tablet or computer, you can download the Kindle software for Android, Apple or Windows for free.

Opinions expressed on Substack and Substack Notes, as well as on Bluesky, Mastodon, Post and X (formerly Twitter), are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.

I was in college in the mid-1970s, majoring in psychology. We had a class where we read and discussed writing relevant to the major, led by a grad student; it was basically an exercise in critical thinking, motivated by the typical undergraduate's teenage joy in finding and pointing out things wrong with adult, supposedly professional writing.

If I recall correctly - and after 45 years I might not - we read something by Wilson, and were predictably unimpressed. At any rate, I did read him back when he was topical, and wound up concluding that his problem was using what scientists call just-so stories, to motivate or explain "obvious" facts, aka things that might lack evidence, but were generally believed at the time of writing.

A contrived example: Suppose I believe that females are, and should be, at all times and places subordinate to males. In fact "everyone" knows this, except maybe a few "crazy" rebels. So to explain the relevance of evolution to human nature, I construct an evolution-based argument, possibly including some more "facts" everyone knows, to show how evolution explains female subordination. Every feminist or semi-feminist who read my book decries me, and rejects evolutionary influence as well.

A few of them know enough about biology and/or human behaviour to recognize that the "facts" are either unproven ("myth", rather than "data") or contradicted by other facts (maybe even supported ones) I neglected to mention. The rest are just jumping on the band wagon, displaying their tribal allegiance, or otherwise demonstrating their own examples of the cognitive deficits inherent to human nature. Those deficits result in progressive loss of nuance; pretty soon I'm being accused of everything any feminist considers evil.

Now I won't say that Wilson left himself open to this. I've seen cases where everything is based on real data, and those who don't like the conclusion still escalate their objections beyond nuance or even accuracy. But in Wilson's case, my memory tells me that the initial reaction was justified. It's amazing how little we knew about animal behaviour at the time, let alone the behaviour of other primates. We also knew precious little about forager lifestyles, yet mostly believed in some model "researched" in the works of Rousseau and/or Hobbes.

I may be misremembering what Wilson had to say for himself, and I certainly didn't follow him - or sociobiology - as it evolved. But while the idea of evolutionary influence on human behaviour was good, IMO the scientific community of the time didn't have the tools to do anything useful with it.

Now we have better knowledge, though much of it is vulnerable to issues connected with the well-known replication crisis, and are beginning to have ideas that may actually be useful.

Popular understanding still tends towards tendentious rubbish - evolution "proves" that we should all live like bonobos - or pan chimpanzees - or gorillas - or maybe bears, wolves or tigers - depending on what behaviour the speaker wants to support. Usually there's been no evolutionary change since some magical date in the past, referred to as "the environment of evolutionary adaptedness", which defines the true good life even today.

The science, however, is getting better. Maybe popular understanding will catch up to today's scientific knowledge in another 50 years, even while the scientific understanding improves farther.