Was COVID-19 Developed in a Lab?

How ordinary people can use the Bayesian approach to grapple with difficult questions like this

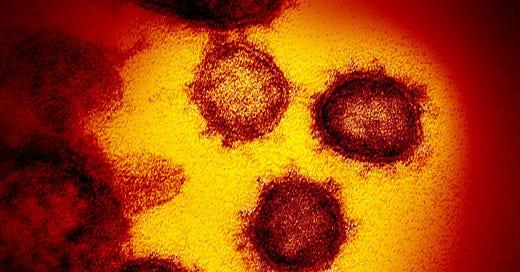

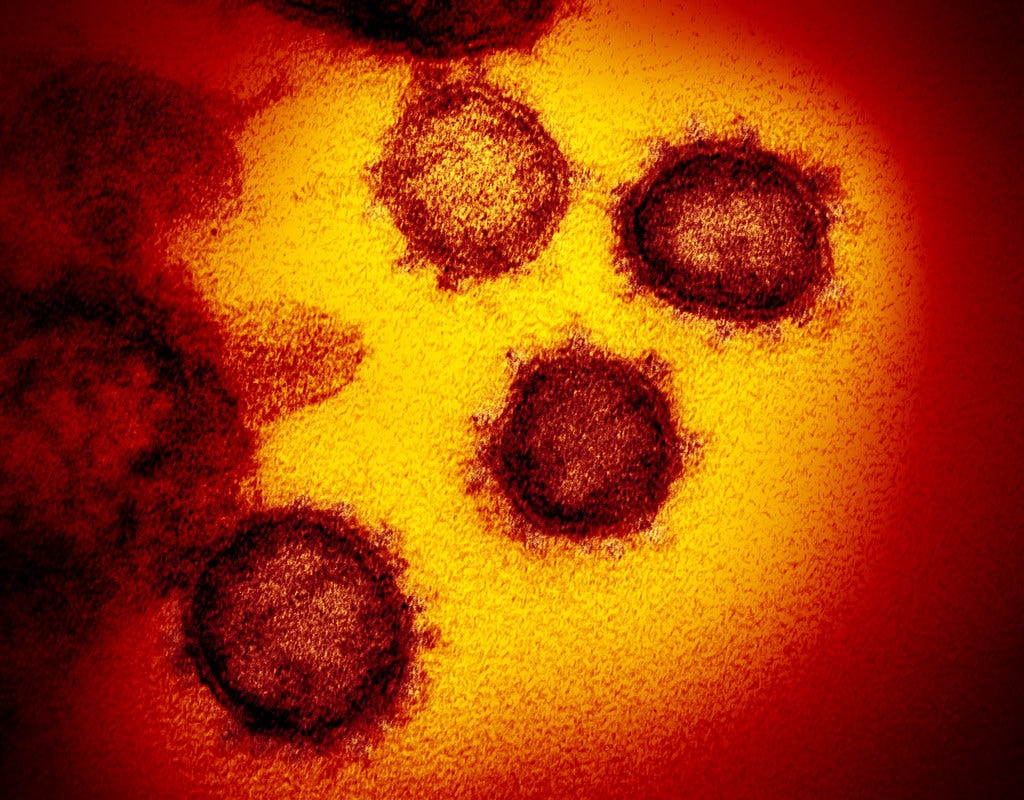

"Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2" by NIAID is licensed under CC BY 2.0

A few days ago, US President Joe Biden asked his country’s intelligence agencies to assess whether COVID-19 originated in a laboratory accident in Wuhan province in China. Around the same time, Facebook said that it would no longer remove posts speculating about a human origin for the pandemic. The idea that COVID might have developed in a lab had slowly been moving into the mainstream for several months beforehand.

The changing status of this idea, from conspiracy theory banned on social media to respectable hypothesis studied by serious people, can be difficult for ordinary people to understand. An approach called Bayesian statistics - the cornerstone of the Sharpen Your Axe project - can help provide useful context. Let me refresh your memory. Bayesian statistics was developed in the 18th Century and has slowly been taking over the world since information about the codebreakers at Bletchley Park using it to defeat the Nazis in World War II was declassified in the 1970s.

Although there is a technical element to Bayesian statistics, a simplified version is based on placing your ideas on a sliding scale of 0 to 100. Try and suspend judgement for the time being. Your starting position isn’t very important. Just take a guess, but assume it will be wrong. Now look at the evidence for and against your idea; and move your idea up or down the scale. If necessary, make a bet or two based on an idea that you think should generate positive results. Adjust its position based on the result. Do this again. And again. And again. If you learn to avoid falling in love with your ideas while adjusting them up and down, you should eventually end up with a more or less reality-based position. Be warned, though, that the process never ends.

A brief description of the Bayesian approach makes it sound very easy. It is actually surprisingly hard to do this consistently. Our natural tendency is to fall in love with our first guess and then defend it vigorously when other people contradict it. The beauty of the Bayesian approach is that it provides us with a system that lets us transcend a poor starting position. It also helps us grapple with the burden of proof: We need more evidence for low-probability ideas.

Let’s apply a Bayesian approach to the idea that scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) might have developed COVID-19, only for it to escape due to an accident. Think back to what we knew in February and March 2020. Both the Sars virus (2003) and the Mers virus (2012) had developed out of naturally occuring infections among bats. Meanwhile, the genome of the latest coronavirus didn’t show any obvious signs of manipulation. At the same time, the WIV was near the source of the outbreak. Any Bayesians would have set the natural theory as the highest probability, while a lab accident would receive a lower probability. Of course, that doesn’t mean that the natural-origin theory was true, just that we would need some very strong evidence for a lab accident in order for both theories to change position on the sliding scale. Biden has just asked the US intelligence community to see if this evidence exists.

The Bayesian approach provides us with some context to understand conspiracy theories. They often involve low-probability positions, such as hostility to science, medicine and vaccines. Their defenders act like the opposite of Bayesians: They are utterly certain that they are right. They try to move backwards from events to alleged causes in an unsophisticated way. Their methodology tends to be poor. They try and discourage others from engaging with non-conspiratorial sources of information.

Despite the difficulties with conspiracy theories, low-probability ideas do sometimes turn out to be true. Conspiracy theorists who hail moments like this as great victories are missing the point. If you dogmatically defend fringe views all the time, you will end up being wrong much more than you are right. On the other hand, if you learn to adjust your views like a Bayesian, you will have a much more solid framework to see why the odd fringe view turns out to be correct, even if many don’t.

Finally, there is a political element to the origins of COVID-19. China is a dictatorship - the Chinese population have no way of getting rid of the country’s top leadership. It doesn’t have a free press. This combination of a dictatorship and press censorship can lead to a culture of secrecy and cover-ups, rather than one of transparency and openness. In this context, it can be hard for observers to get the information we need to help us change our views quickly. Our initial positions on the sliding scale can get entrenched. It is easy to see why Facebook sought to ban a low-probability view that was getting spread enthusiastically by anti-globalists, even if that call looks terrible in retrospect.

Sharpen Your Axe is a project to develop a community who want to think critically about the media, conspiracy theories and current affairs without getting conned by gurus selling fringe views. Please subscribe to get this content in your inbox every week. Shares on social media are appreciated! If this is the first post you have seen, I recommend starting with the critical-thinking rabbit hole.

[Updated on 10 March 2022] Opinions expressed on Substack and Twitter are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.