Notes on Value Creation

A key concept in business and finance that should be applied more widely

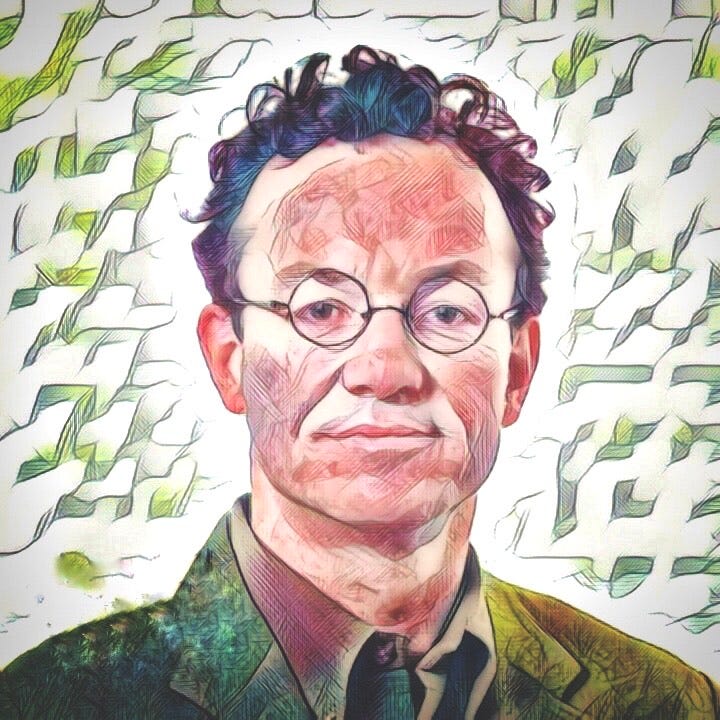

This week’s column is dedicated to Charlie Welsh

If you go to any major newsroom, you might be surprised to see how few journalists you find who belong to the so-called “generation X.” This includes people born between 1965 and 1980. I was born in 1970 and am a rare exception to the trend, with 28 years of reporting experience under my belt so far. Most of my colleagues are much younger. Older colleagues are few and far between.

In my experience, journalism was extremely hard to break into in the 1990s, but was then devastated by digitalization in the early 2000s. Many of my peers failed to get a foot in the door when they were young; and too many of those that did crashed out of the profession* and moved into corporate communications or public relations after Google destroyed advertising revenues.

I was lucky enough to buck both trends. First of all, in 1995, I spotted an advert for a job as a news reporter at Dow Jones Newswires. The name of the lady in human resources was spelt wrong. Some 200 people applied for the job, but I was the only one to call and check the spelling. I was 25 at the time and struggling to make a name for myself. A single stroke of good fortune at the right time meant that I was able to gain plenty of experience in real-time news as a young man, become a foreign correspondent in Madrid at 27 and regularly get my byline into both the Wall Street Journal and the now defunct Wall Street Journal Europe.

Secondly, by the time I was in my 30s, I’d realized that I couldn’t rely on a conventional career path, which would probably have involved eventually moving onto a newspaper. The internet was going to change everything. I’d had the chance to see newspaper journalism up close during my 18 months as a Lobby reporter in the House of Commons with Dow Jones Newswires. I gradually realized that the reporters with newspaper jobs had put up high barriers to entry to protect themselves from healthy competition from newcomers; and few of them seemed to have realized that Google’s AdWords, launched in 2000, was going to change their world in a number of unpleasant ways.

Meanwhile, I’d also come to believe that the fierce competition between Dow Jones Newswires, Reuters and Bloomberg around the turn of the century would lead to a process of commoditization, which would be uncomfortable for the purveyors of real-time financial news.

I got married in 2001 and my wife and I started a family soon afterwards. Around this time, I conciously sat down and tried to work out how to develop some longevity in the news business despite the new circumstances. I came to realize that one underlying problem with Lobby reporting was that there were too many reporters chasing too few stories. This gave the upper hand to politicians and their advisors, who could have fun and games every time they wanted to announce (or leak or suggest) new policies. I decided to try and flip the formula and find an area with few reporters chasing plenty of stories, preferably in a field with little danger of commoditization that didn’t depend on advertising revenues. I wrote a shortlist of potential beats. Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) was at the top.

Shortly afterwards, I spotted an advert in The Guardian from a London-based startup called Mergermarket that was looking for M&A reporters. I applied. The founder, Charlie Welsh, was an intense and scruffy Anglo-Canadian a few years older than me. He had launched the startup in 1999/2000 with a focus on business intelligence and data. It had survived the dot-com crash, but this also meant that it would have to count on its own revenues from subscriptions instead of getting more funding from outside investors. Charlie wanted to move into investigative reporting. We came to a deal and I started as senior reporter on the company’s first investigative project in 2002.

I remember telling some friends and colleagues from Dow Jones Newswires that I was leaving a company with more than 100 years of history to join a small, scrappy startup with offices in an edgy part of East London. My role would be to churn out scoop after scoop. My wife was pregnant with our first child at the time. More than one former colleague told me that I was completely insane. Of course, with the benefit of hindsight, they would nearly all crash out of journalism in the following years, while Mergermarket went from strength to strength**.

The group eventually changed its name to Acuris while keeping the Mergermarket brand for its flagship product; and achieved unicorn status in 2019. I moved to Barcelona in 2005 to help set up and run the company’s Iberian coverage and have been here ever since.

In Mergermarket’s early days, I asked Charlie why the publication didn’t have a style guide (something that is fairly standard practice in journalism). His answer surprised me, but I learnt a lot from it. He told me that if he decided to authorize a style guide, two or three journalists would disappear into a meeting room for six months and have lots of fun arguing about Oxford commas and whether to write “specialization” or “specialisation.” He said that the end result would add maybe 1% value to readers, at best. However, if the journalists instead focussed on breaking and editing scoops, they would produce much more value for readers.

Charlie was gently introducing me to two very important concepts. The first is opportunity cost. Economists say that the cost of doing an activity is relative to the lost chance to do an alternative activity. So, I am writing this blog post on a wintry Sunday evening in late January while my wife and daughters are busy with their own projects. My alternatives might include watching a film or reading a good book. For me, sharing my thoughts with the world is worth the cost of not watching television or spending some quality time with my Kindle.

The second concept is value creation. This idea has been mostly neglected by academic philosophers, with the honourable exception of Robert Nozick. It is most associated with thinkers like Karl Marx and Ayn Rand, who have almost nothing in common with each other. The idea behind value creation is to create a product or service that a third party finds useful.

So, in Charlie’s example, breaking a scoop about M&A is actionable information for a wide range of financial professionals, from investment bankers looking for deal mandates to private equity executives thinking about an investment opportunity.

The concept of value creation is very widespread in the worlds of business and finance, largely because it is relatively easy to measure in both fields. It can be much fuzzier in other areas, like education. We can measure the impact of a sales rep closing a deal on his or her company’s bottom line; but it is much harder to measure the impact of a school teacher providing a positive example to a kid growing up in tough circumstances.

Despite this fuzziness of the concept in many areas, value creation is an incredibly important idea. I believe that we need to find ways to incentivize it so that entrepreneurs, innovators and artists can run experiments on new ways to create value, fail, pick themselves up and try again. We should appreciate value creation wherever we find it, not just in areas where it is easy to measure, like business and finance. We also need to be clear-eyed on the difference between creating value and running a grift (basically, pretending to create value).

The idea of value creation can also be important for people who are struggling economically. If you want to bring in more money, then you should think hard about how you can create value for a certain group of people. If you create enough value for this community, getting back a small percentage in return can make a significant difference to your bank account.

It is important to reiterate that we create value for other people, not for ourselves. This point is rarely discussed, but it is significant. Creating value for others is often based on an outward-looking attitude that emphasizes solving other people’s knotty problems.

At its best, value creation can create a link between two core values that we have discussed before - personal freedom (particularly the freedom to innovate without asking for permission first) and solidarity (in this case, solving other’s people’s problems for them). Of course, in the face of the populist threat to democratic values, we need to nurture strong institutions so these values can flourish. Without the peaceful transition of power, Mafia states can evolve, which can create difficult circumstances for people interested in value creation.

Finally, the purpose of this week’s column isn’t to write a hagiography of Charlie. He could be argumentative and difficult. He sometimes shouted at people. Having said that, I miss our conversations and his insights into how journalism was changing and needed to change. I am grateful for the platform he created, which allows a select group of financial journalists to create value for M&A professionals and investors. May he rest in peace! The comments are open. See you next week!

*I call news reporting a profession in the passage above, but really it is an artisanal craft.

**Algorithmic trading devastated the wires in the early 2000s. A trading algorithm only cares about numbers. A beautifully written summary of what happened half an hour ago might help human traders take a position, but it is completely irrelevant to an algorithm. If anyone I knew saw this coming in the nineties, they certainly never mentioned it to me!

Funnily enough, a company called ION was founded by a former trader in 1999 to revolutionize trading through the use of algorithms. The company ended up buying Mergermarket’s parent company, Acuris, in 2019. The combination of algorithmic expertise with the kind of journalism that Charlie nurtured is proving explosive… but that is an issue that I think about from Monday to Friday and is not necessarily a core topic for my Saturday-morning blog.

Further Reading

The Future and Its Enemies by Virginia Postrel

Further Reading 2

The US Energy Department says that COVID-19 was probably the result of a lab leak

Sharpen Your Axe’s take on this issue from May 2021

A refresher on the Bayesian approach, which can help us track low-probability possibilities like this one

Sharpen Your Axe is a project to develop a community who want to think critically about the media, conspiracy theories and current affairs without getting conned by gurus selling fringe views. Please subscribe to get this content in your inbox every week. Shares on social media are appreciated!

If this is the first post you have seen, I recommend starting with the second anniversary post. You can also find an ultra-cheap Kindle book here. If you want to read the book on your phone, tablet or computer, you can download the Kindle software for Android, Apple or Windows for free.

Opinions expressed on Substack, Twitter, Mastodon and Post are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.

Thanks Ruper for this vibrant story: it's much more than an article for us MM guys, in Italy we could say it's a piece of heart!