The Deep State and the Rule of Law

What is the "deep state"? And what does Trump mean when he says the words?

"Deep State" by canonsnapper is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

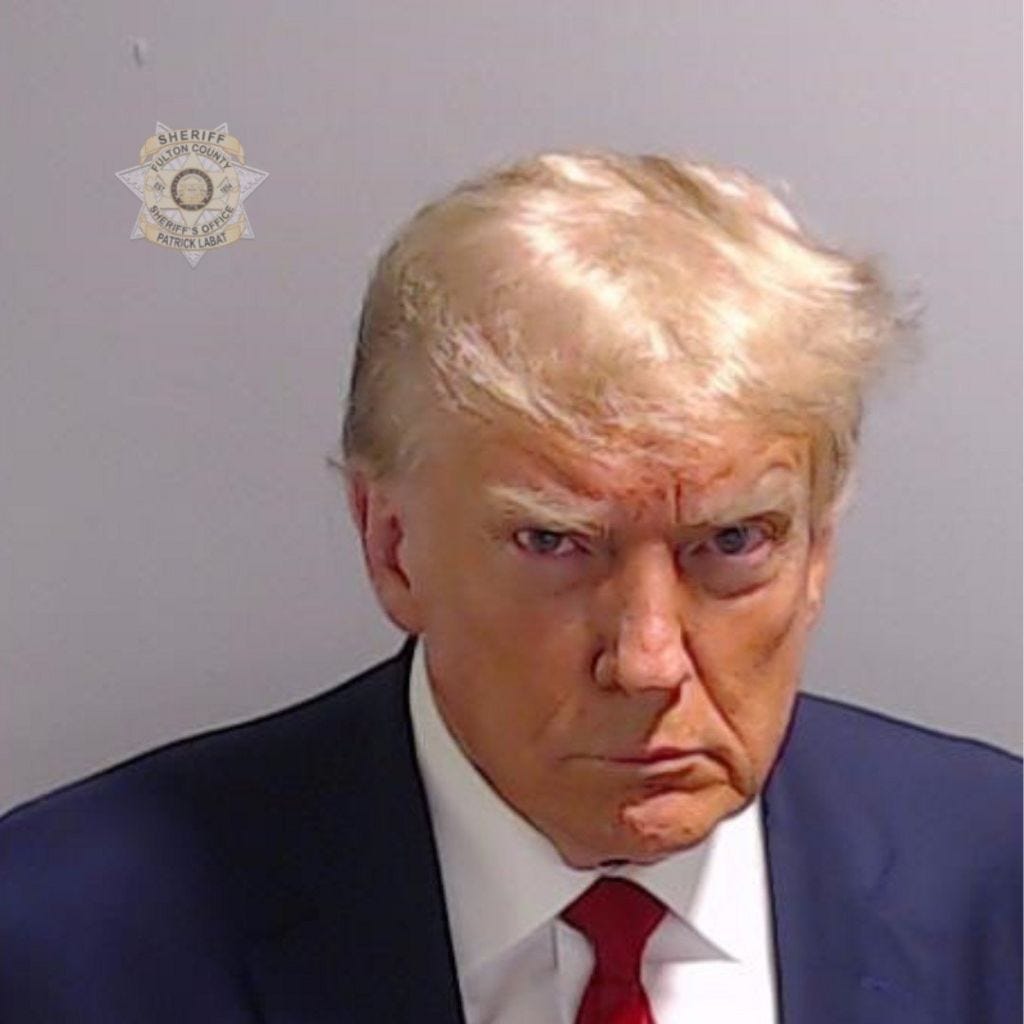

If you haven’t heard the words “deep state” yet, I can guarantee that you will in the weeks and months ahead. Disgraced former US President Donald Trump is throwing the phrase around as a central part of his defence against multiple lawsuits surrounding his coup attempt in 2021 and other issues.

The phrase was originally coined in Turkey to refer to “high-level elements within the intelligence services, military, security, judiciary, and organized crime,” who often work together, in the words of author and former US Congressional aide Mike Lofgren. He published a book on what he sees as the US deep state in 2016 after retiring from the government.

The term is often used by conspiracy theorists, including Trump, who use it as a proxy for the shadowy elites that they believe sit behind elected officials and pull the strings of world affairs. However, Lofgren is more prosaic: “My analysis of the Deep State is not an exposé of a secret, conspiratorial cabal. Logic, facts and experience do not sustain belief in overarching conspiracies and expertly organized cover-ups that keep those conspiracies successfully hidden for decades.”

Instead, Lofgren describes “a state within a state” that slowly evolved over time. He sees the 1970s as a key time for the ascendance of a supersized bureaucracy, helped by politically focused foundations. It continued to grow in the 1980s despite Ronald Reagan’s rhetoric about limited government.

Logren sees 2013 as a threshold. It was when Jim DeMint resigned as a US Senator to become president of the Heritage Foundation. The politician claimed at the time that his new job would be more influential than his old one. Whether or not that is true, the new role was certainly more lucrative.

Lofgren describes the visible parts of the US government (including the White House and the Capitol) as the tip of an iceberg. The peaceful transition of power is more important at the top than it is at the base, he says. He argues that the deep state includes national security and law enforcement agencies, plus part of of other branches, such as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court and some members of the Defense and Intelligence committees. It also includes links to Wall Street and Silicon Valley, he argues.

At its core, Lofgren’s analysis is based on the idea that bureaucracies often serve their own interests above all else. This observation is unlikely to shock anyone other than very committed socialists, who want to abolish markets and replace them with a large bureaucracy to run the economy.

In fact, there is a whole branch of economics called public choice theory, which looks at how bureaucrats tend to protect their own interests. Randy T. Simmons has written a beginner’s guide to the subject. He describes it as the application of economic reasoning to the study of collective or public choices. Elected officials and bureaucrats might believe themselves to promote the public interest, while they are actually promoting solutions that benefit them personally, he says.

One of the best case studies I have seen of self-serving bureaucracies is Robert Coram’s biography of Robert Boyd, a maverick genius who started his adult life as a fighter pilot before becoming a leading military theorist. His hardest fight was to get the Pentagon to approve stripped down fighter jets without adding lots of bells of whistles, which would be good for departmental budgets but hurt the basic principles of the design. The book is a gripping read.

On the face of it, bureaucrats protecting their own narrow interests seem very different from the prosecutors who are investigating Trump’s actions before and during the Capitol riots on 6th January 2021. These include Fani Willis, the daughter of a former Black Panther who was elected to be district attorney for Fulton County, Georgia, in 2020. Fulton County holds most of Atlanta (one of the US cities with the highest percentage of African American residents) and she is the first woman to hold the post. As an elected official, she is an unlikely member of what Lofgren describes as the deep state.

Image from Fulton County Government website

Willis wants to see if the former president is guilty of racketeering, among other crimes on the statute book. Georgia passed its own Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act in 1980, ten years after the Federal government introduced the rules at the national level to fight organised crime.

Much of the evidence is already in the public record, including Trump’s infamous tweet about the upcoming demonstration at the Capitol, which said: “Be there, will be wild!” Following the demo, rioters broke into the building and hunted Trump’s Vice President Mike Pence, while chanting that they wanted to hang him. Trump had incorrectly claimed that Pence could overturn the 2020 election result and accept his fake electors from Georgia and elsewhere.

If prosecutions by Willis and others aren’t deep state actions, what are they? As we have said before, Trump is a populist. He sees himself as the living embodiment of the “will of the people.” This means that he sees any attempt to curtail his power as illegitimate, whether it involves an unsuccessful election campaign, a law preventing him from storing secret documents in the bathroom of his favourite golf course or a court case after he has ignored an inconvenient law.

Conspiracy theories about a stolen election act as bodyguards to Trump’s strange worldview. His allegations about the “deep state” are nothing more a convenient piece of bullshit to cover his tracks, often combined with racist rhetoric. His practice of ignoring feedback means that liberal democracy (a negative system) cannot work as it is meant to.

We have discussed before how liberal democracy has three pillars: the rule of law, the peaceful transition of power based on elections and individual human rights. Of the three, the rule of law is the oldest. It traces its roots back to Greek and Roman philosophy, with influences from the Hebrew Bible, although other cultures have developed similar ideas independently over the centuries.

A Scottish Presbytarian minister called Samuel Rutherford outlined the theory behind the idea in 1644. His case that rulers should obey the law helped set the scene for John Locke, an Englishman who developed his philosophy in exile in the Netherlands. He published an influential defence of the rule of law in 1689 and became known as the father of liberalism as a result, inspiring the Founding Fathers of American democracy almost a century later.

Portrait of Locke by Godfrey Kneller - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35691670

In modern times, the basic idea of the rule of law is that our rulers have to obey the same rules as the rest of us. These laws should be as universal as possible. They should be written down and publicly available. The process to change unpopular laws should be clearly outlined ahead of time.

In 1748, a generation before the Declaration of Independence in the US, French thinker Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu, developed Locke’s ideas about the separation of powers, which was to become a key part of the rule of law. Since then, supporters of liberal democracy, including the Founding Fathers, have paid homage to the idea that proposals for new rules should be written by the executive branch before being debated, reviewed and approved by the legislative branch and executed by the judiciary, which includes attorneys like Willis.

Understanding this point provides us with a skeleton key to understand Trump’s attitude. After leaving the executive branch, he openly broke the law and is now trying to discredit the judiciary that is seeking to punish him. As a populist, a narcissist and a grifter (what the Founding Fathers would have called a demagogue), Trump obviously believes that he is above the law and his actions should be judged differently from those of other people.

In fact, the system is working as it is designed to work - the rule of law and the separation of powers are meant to prevent what Locke, Montesquieu and the Founding Fathers would have described as tyranny. The word is old-fashioned, but there can be no doubt that in 2021 Trump wanted to install himself as a tyrant (a ruler who can govern in arbitrary ways without obeying pre-existing rules).

So, whenever Trump says the words “deep state” in the future, please substitute the phrase with “the rule of law” in your head. You will find his running commentary on his legal issues begins to make much more sense. We will let Locke have the last word. He wrote: “Where law ends, tyranny begins.” The phrase is still engraved on the Department of Justice’s main building in Washington DC. The comments are open. See you next week!

Further Reading

The Deep State by Mike Lofgren

Beyond Politics by Randy T. Simmons

Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War by Robert Coram

Sharpen Your Axe is a project to develop a community who want to think critically about the media, conspiracy theories and current affairs without getting conned by gurus selling fringe views. Please subscribe to get this content in your inbox every week. Shares on social media are appreciated!

If this is the first post you have seen, I recommend starting with the second anniversary post. You can also find an ultra-cheap Kindle book here. If you want to read the book on your phone, tablet or computer, you can download the Kindle software for Android, Apple or Windows for free.

Opinions expressed on Substack, Twitter, Mastodon and Post are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.