Unintended Consequences of the World's First Bestsellers

How the printing revolution and the Protestant Reformation paved the way for modern, secular societies

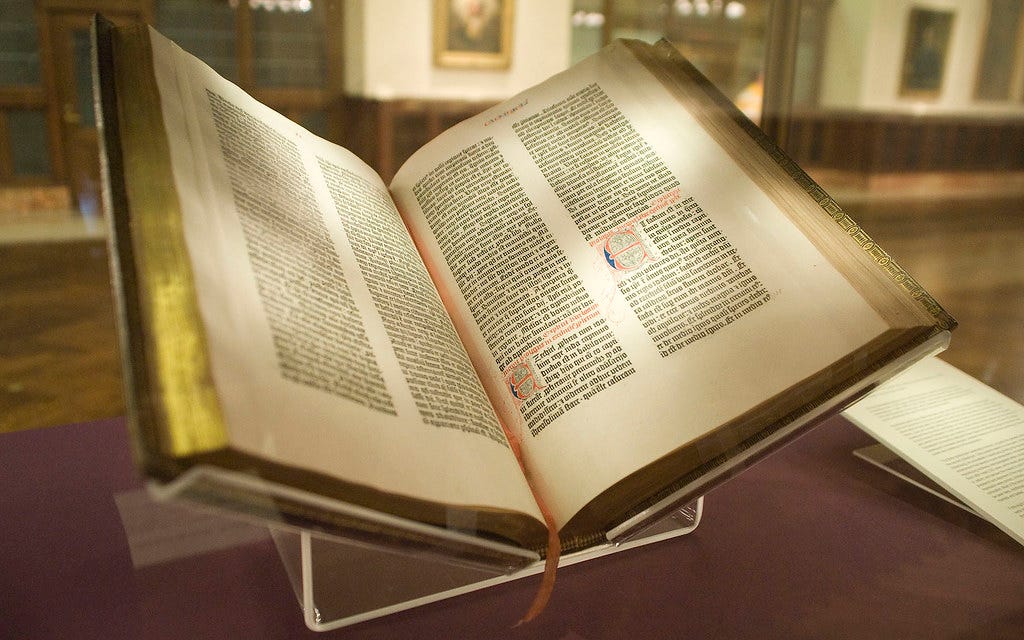

"Gutenberg Bible" by NYC Wanderer is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

In 1439 or 1440, a German goldsmith called Johannes Gutenberg became the first European to perfect a movable type printing press in Mainz in the Holy Roman Empire. In 1882, some 442 years later, German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche famously proclaimed for the first time: “God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.”

This week’s blog post will look at the intimate connection between the printing revolution triggered by Gutenberg and the death of traditional religious belief noticed by Nietzsche. First, though, let’s backtrack to Gutenberg’s great discovery. Like gunpowder, the printing press had its roots in China. There are stories about a sage in the 480s who blew on paper to form characters. He was executed for his troubles. Later historians think he might have discovered printing but sought to mystify its origins.

By the seventh century, Buddhists were using woodblocks to create sacred documents. The technique spread far and wide and was common in Europe by the 1300s. Movable type printing, which was quicker and more durable than woodblock printing, was discovered in China by Bi Sheng around 1041. However, the technology was neglected for the first 300 years and never fully replaced more traditional methods. It seems to have spread into Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries, but the details are murky.

Gutenberg published a Bible in Mainz between 1452 and 1454 using movable type. Competitors set up printing presses throughout Europe. By 1500, there were 1,000 printing presses from London to Kraców, producing millions of books. European imperialists took the tech to Mexico by 1544 and to Goa in India by 1556.

Our story now returns to Wittenberg, around 230 miles from Mainz but less than 40 miles from Nietzsche’s childhood home near Leipzig. Martin Luther, a professor of moral theology at the local university, published his Ninety-five Theses on how to reform the Catholic Church in 1517. Most notoriously, he said that the Church should stop selling indulgences, or certificates that were meant to reduce time in purgatory. The publication of the first edition is traditionally celebrated as the start of the Protestant Reformation.

Copies of the book were soon printed in both Latin and German. In modern terms, Luther’s ideas went viral throughout the Holy Roman Empire and then Europe, in a way that previous reformers like the Waldensians had failed to achieve. The Pope asked the head of Luther’s religious order to stop spreading his ideas about a reformed church; while some hardline Catholics called for Luther to be burnt at the stake. Luther persisted. He wrote short and inexpensive books and pamphlets in German, which became the first true bestsellers. Luther himself said that the printing press was a gift from God.

Although Luther never originally intended to create a schism in Christendom, his ideas split Europe down the middle. Wars of religion waged across the continent through the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Estimates of the death toll from the Thirty Years War in the Holy Roman Empire alone ranged from 4 million to 12 million.

Our story now turns to the Dutch Republic. Amsterdam is some 260 miles from Mainz and just over 400 miles from Wittenberg. Like both cities, it used to be part of the Holy Roman Empire. Dutch humanist theologian Desiderius Erasmus paved the way for the Reformation by criticising the Roman Catholic Church, although he kept his distance from Luther. The Reformation took a couple of decades to catch on in the Netherlands, but the ideas of John Calvin and radical Protestantism both caught hold.

From 1566 to 1648, the Netherlands engaged in the Dutch Revolt (also known as the Eighty Years’ War) against the country’s Catholic rulers in far-away Habsburg Spain. The Protestant-dominated Dutch Republic was declared in 1588 and was finally recognized by the Spanish in 1648.

Religion became very diverse in the Netherlands during the war. The majority of the population were Calvinists, but they weren’t united. There was a civil war between Arminians and Gomarists (two different branches of Calvinism) in the 1610s. Other Christian sects were tolerated, sometimes a little more and sometimes a little less, including Catholicism and radical Protestants. The Netherlands was also home to a sizeable Sephardic Jewish community, whose ancestors had been expelled from Catholic Spain in 1492.

After generations of bloodshed and war, inhabitants of the Dutch Republic often developed a live-and-let-live attitude that feels very contemporary and cosmopolitan to those of us who live in the 21st century. One interesting aspect was that the state developed a hands-off approach to how ordinary people lived, which allowed innovation to flourish for the first time in human history.

Baruch Spinoza, one of the great Enlightenment thinkers, was born into a Sephardic family in Amsterdam in 1632, towards the end of the Dutch Revolt. He argued that philosophers should treat the Bible as if it were an ordinary book - a breakthrough that would have been almost inconceivable before Gutenberg began the printing revolution. In 1656, at the tender age of 23, he was expelled from the Jewish community for his heretical ideas.

For most of human history, it would be unthinkable for someone to continue to live and work in a major city without the support of a religious community. Spinoza left Amsterdam for a while, but eventually quietly returned. He continued to live as a private scholar and a lens grinder, much to the surprise of his contemporaries. He often feels like the first modern man, although his texts in Latin and mostly published posthumously can be a little challenging for a reader without a background in philosophy.

English philosopher and physician John Locke fled to the Dutch Republic in 1683 after being accused of a plot. Although Spinoza had died a few years before, Locke made friends with freethinkers and dissident Protestants who had known the older philosopher. During his five years in Utrecht, Amsterdam and Rotterdam, he wrote his famous essay, A Letter Concerning Toleration, which would earn him his reputation as the father of liberalism.

England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688 was effectively a Dutch takeover. Locke accompanied Queen Mary back to England from the Netherlands and published his thoughts on religious toleration in 1689. Exactly 100 years later, his beliefs formed the cornerstone of the American Revolution.

Although Locke argued against atheism in his key text, Spinoza’s example of living outside a religious community had already let the cat out of the bag. The first openly atheist writer we know about was Matthias Knutzen, a German who was writing in Locke’s lifetime. He was last seen in Jena (nearly 160 miles from Mainz), where he distributed hand-written atheist pamphlets before disappearing from the historical record. He claimed there were small groups of Conscientarians (or atheists) in cities like Amsterdam, Hamburg and Jenna, as well as Paris and Rome.

Many thinkers followed in his footsteps, not least the great Scottish skeptical philosopher David Hume, who lived in the 18th century. French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace - one of the founders of Bayesian statistics - was once asked by Napoleon Bonaparte where God fit into his probabilistic system. He is said to have replied: “Sir, I have no need of that hypothesis.”

So, by the time that Nietzsche announced the death of God, the printing revolution had already created the conditions that led to religious pluralism. The first result was bloodshed, but the seeds of toleration began to appear in the Netherlands, loosening the hold of religion on peoples’ worldviews. Spinoza showed that it was perfectly possible to live without being a member of a religious community; and later writers had shown that it wasn’t necessary to tip your hat to traditional religion before doing good work. Ordinary people noticed that if all your neighbours had different beliefs, it might not be necessary to take your local religious leader quite so seriously.

However, this isn’t the full story. In the 140 years since Nietzsche announced the death of God, we have seen time and time again what theologians call “a God-shaped hole” at the heart of modernity. Author Karen Armstrong points us in an interesting direction by discussing the difference between mythos and logos in the pre-modern world. Mythos is concerned with what is timeless and essential (think religious parables); while logos is pragmatic and practical (such as instructions on thinking critically). The world that has emerged since Gutenberg’s innovation has mostly been very bad at mythos while being very good at logos.

Once we understand the distinction, we can see that ideologies like Marxism and apocalyptic environmentalism on the left or QAnon and bitcoin maximalism on the right are tapping into mythos rather than logos. They are designed to give transcendent meaning to the lives of people who are struggling to live in a world without God. Arguing with followers of any hedgehog-like mythos is guaranteed to trigger cognitive dissonance on both sides.

There are healthier ways of incorporating mythos into your life than signing up for an intellectual cult. Authors like Neil Gaiman, Ursula Le Guin and Philip K. Dick developed deep skill in mythos-based storytelling. Hollywood has been grappling with our need for mythos for years and the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is just the latest attempt. At the same time, mindfulness meditation is a useful way of giving our logos-based mind a well-deserved rest for a short while.

Finally, atheists, agnostics and non-believers shouldn’t be too confident that the revolution unwittingly wrought by Gutenberg, Luther and Spinoza is by any means over. Religious believers tend to have more children than others, which gives their belief systems an advantage over the course of many generations. And immigration can yield strange results, such as making London the most religious city in the UK. A secular future is by no means assured. The comments are open. See you next week!

Further Reading

Spinoza: A Life by Steven Nadler

The Second Treatise on Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration by John Locke

The Battle for God by Karen Armstrong

Sharpen Your Axe is a project to develop a community who want to think critically about the media, conspiracy theories and current affairs without getting conned by gurus selling fringe views. Please subscribe to get this content in your inbox every week. Shares on social media are appreciated!

If this is the first post you have seen, I recommend starting with the first-anniversary post. You can also find an ultra-cheap Kindle book here. If you want to read the book on your phone, tablet or computer, you can download the Kindle software for Android, Apple or Windows for free.

Opinions expressed on Substack, Twitter, Mastodon and Post are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.

A couple of extra points:

1. Translation of the Bible into the vernacular and dissemination through the the movable type printing press were probably key to the Protestant reformation and probably therefore later atheistic ideas. Once non-Latin speakers were able to see for themselves the true nature of the Bible as a text, they were able to analyse and challenge the Church’s interpretation. Translations such as the Wycliffe and Huss Bibles were available for those few who could access them but Guttenberg’s press allowed much wider dissemination, as well as of the original Greek and Hebrew texts.

2. Muslims could be said to be early adopters of paper technology being responsible for its transmission from China in the 8th century. By contrast, the use of moveable type printing was not welcomed in the Muslim world, partly due to difficulties in reproducing Arabic script and an aesthetic appreciation of the beauty of writing. This was not to change significantly until the 19th century.