Taming Lions

The upcoming election in Spain is likely to bring populists into power, no matter which side wins

“A plague o' both your houses!”

Mercutio in Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

Spain is facing a snap general election on Sunday 23 July. Incumbent Prime Minister (PM) Pedro Sánchez, of the centre-left Socialist Party, is going toe to toe with the leader of the opposition, Alberto Núñez Feijóo of the centre-right Popular Party (PP). Neither is expected to win a majority, although Feijóo is ahead in the polls after winning an informal auction to capture the votes of a mismanaged liberal party as it lay on its deathbed.

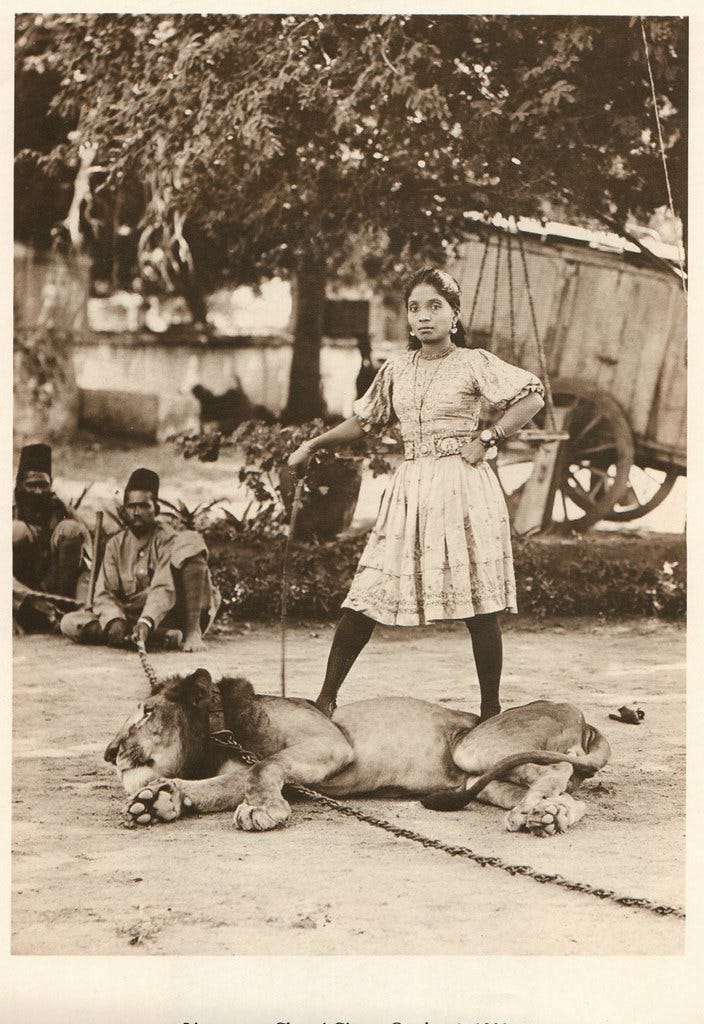

"lion tamer 1901" by janwillemsen is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Democratic Spain has no tradition of grand coalition deals across the left and right at the national level. Patriotic abstentions from an institutionalist perspective are just a fantasy at the moment. That means that many voters, particularly floating voters, will have to think long and hard about which potential post-election pact is likely to be more toxic if neither side wins a majority.

Sánchez gained power in June 2018 as a result of a vote of no confidence in the PP’s last PM, Mariano Rajoy, following an outrageous corruption scandal dating back to the conservative party’s long period of dominance during the boom years between 1996 and 2004.

To get the no-confidence vote over the line, the Socialist leader put together a so-called “Frankenstein alliance” of parties to his left and separatist parties, some of which (fairly bizarrely) identify as being left-wing Catalan or Basque nationalists - clearly a contradiction in terms to most non-aligned observers. The only idea that unites the coalition members is hostility to the PP, which is often smeared as being a fascist party, despite sitting well to the left of the UK Conservatives or the US Republican Party.

Meanwhile, if Feijóo wins the election without a majority, his best bet will probably be to forge an alliance with Vox, a political party that was formed in 2013 from some of the most right-wing elements in the PP. The PP had found a winning formula by the mid-1990s by applying a “big tent” approach to the right, with liberal conservatives leading a wide coalition spanning non-ideological moderates, centrists, liberals, regionalists, Christian democrats, social conservatives, Spanish nationalists and outright reactionaries. Former PM José María Aznar even did deals with right-wing Catalan and Basque nationalists during his long stint in power.

You will notice that I deliberately haven’t described either the parties to the left of the Socialists or Vox. The description of either side is complicated. Supporters of Sánchez describe the parties to his left as “the left of the left.” Some claim that the PM has implemented a traditional alliance of socialists and social democrats. Some of the least sensible voices position the parties to Sánchez’s left as some kind of “real left,” while the Socialists are seen (rather improbably) as wishy washy centrists.

Meanwhile, opponents of the left can get a little hysterical about the role of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) as an active player in the coalitions on the left side of the spectrum. The PCE has been engaged with moderate Eurocommunism for decades. Please note this is not an endorsement of the PCE!

At the same time, some people on the right will often try to describe Vox, which is led by former PP member Santiago Abascal, as being an old-school conservative party. This view depends on seeing the PP as wishy washy centrists. Some of the loudest voices on the right-wing side of the aisle even describe the PP as social democrats, which is frankly silly.

Meanwhile, opponents of the right can get a little shrill with claims that Vox is an outright fascist party. It is true that some of its leaders have their roots in neo-fascist party Phalanx (Falange) and it certainly has fascistic tendencies, to put it mildly. In general terms, though, the party feels more Giorgia Meloni than Benito Mussolini at the moment. Please note that this is not an endorsement of Vox!

Populism can hold the key for describing some of the potential coalition members on the far sides of the spectrum. Populism is a “thin ideology” that can be applied by narcissistic leaders on the left and the right, who see themselves as the true voice of the people. This makes it very difficult for populists to accept the legitimacy of their opponents or of actually existing elites. Populists who win elections often erode the institutions of liberal democracy in a process called democratic backsliding.

Sánchez’s main coalition ally since 2020, a left-wing party called Together We Can (Unidas Podemos - UP), certainly deserves the description as being a populist left party. It was founded with the name We Can (Podemos) in 2014 by a university lecturer and activist called Pablo Iglesias, who regularly cited populist theorists like Carl Schmitt (a paid-up member of the Nazi Party whose criticisms of liberal democracy resonated with left-wing populists around the world) and his Argentine follower Ernesto Laclau.

In 2018, Iglesias went to Argentina and declared that he was a Peronist. He had earlier floated the idea of Spain defaulting on its debt, an approach which had already led to terrible consequences in Argentina. Around the same time, members of neo-fascist party Phalanx complained that Podemos had stolen many of its policies.

Of course, populists aren’t very good at competent governance, as many Argentinians have found out the hard way. Iglesias’ wife, Irene Montero, is the equality minister in the coalition. Her team wrote a sloppily drafted sexual consent law in 2022, which caused outrage across Spain when it was used to reduce sentences for more than 700 sex offenders and let more than 70 rapists out of prison.

Two of the parties that have supported Sánchez without entering a formal coalition are very controversial in most of Spain. One is the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), which backed a failed separatist coup attempt in the region in 2017. The other is Bildu, which combines populism and nationalism in the Basque Country. It is led by a former terrorist from Basque Homeland & Liberty (ETA) and many of its deputies are open apologists for terrorism, the most toxic form of populism. ETA disbanded in 2018 after killing more than 800 people between 1968 and 2010.

Iglesias worked hard to position UP as a bridge between ERC/Bildu and the Socialists in the early days of the coalition. As time has gone by, Iglesias has moved out of frontline politics and into the media. He has gradually lost influence on the movement he once led, particularly after UP failed to live up to its promises to change the whole of society from top to bottom.

Iglesias’ ultra-ambitious approach, which he famously characterized as“storming the heavens,” gained some traction as Spain nursed its bruises from a long recession a decade ago. His party hit an absolute high of 5.2m votes in the 2015 election (as Podemos) and a relative high of 21% of the vote in 2016 (as Unidos Podemos). Support for the populist left dropped sharply in the following years as formerly young and disgruntled voters found jobs and started families in improved economic circumstances. Reforms implemented by Rajoy’s economic team between 2012 and 2018 turned the tables.

Another UP-nominated deputy, one of Sánchez’s deputy PMs called Yolanda Díaz, has gained power in the movement as Iglesias’s influence has waned. A paid-up member of the PCE, she has created a new platform called Addition (Sumar), which aims to provide a framework for various left-wing parties and nominally left-wing separatists to work together, including UP and the PCE. She insisted on excluding Iglesias’ wife Montero from the lists for the next election as a condition for a deal with UP - a sign that she is able to accept feedback on badly implemented plans, even if she is not quite reflective enough to realize that communism is a failed ideology.

Díaz is much less interested than Iglesias in populist culture wars. Iglesias tends to be better at picking fights than at winning them - right-wing populism punches harder than left-wing populism. Instead, Díaz wants to emphasize reforms that are meant to improve the life of ordinary people, even if her anti-market bias means that many of the reforms are destined to fail (such as rent controls - a misguided policy that neo-fascist party Phalanx has traditionally pitched).

It is interesting to note that Díaz has signed on Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz to advise on Sumar’s manifesto. Describing her approach as populism seems a stretch, although Sumar will, of course, include many populists in its lists.

Meanwhile on the right, Abascal’s Vox is often quick to question the legitimacy of Sánchez’s governance, which takes it down a slippery slope. Its leaders see Hungarian populist strongman Victor Orbán as their model. They also share many of the traits of other right-wing populists, like Meloni and Donald Trump, such as being concerned by “wokeness” and worrying about masculinity and traditional values, with a frankly bigoted attitude to immigrants and members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) community. Its leaders can’t quite decide whether they believe in Spanish nationalism or ultra-liberalism, which are contradictory worldviews.

Describing Sumar and Vox as far right and far left makes sense, respectively, but the problem is that probably neither of them would accept the label. This isn’t the 1930s, after all. I think hard left and hard right work much better. Are the labels perfect? No. However, I think this phrasing will do for now, just about. It is worth remembering that the hard left tends to be economically illiberal, while the hard right tends to oppose the advances of social liberalism. Both have populist tendencies.

The problem for Spain’s soft left is how to sell a new deal with the hard left and separatists as being acceptable while demonizing the whole of the right side of the spectrum. The problem for Spain’s soft right is to sell a deal with the hard right as being acceptable while demonizing much of the left, along with allegedly left-wing separatists.

Whether you are on the left or the right, I think we can agree that neither tactic is particularly healthy in a liberal democracy, which should be based on healthy competition, sensible coalition deals and the peaceful transition of power combined with loyal opposition. Demonizing the other side while cutting deals with extremists is far from optimal.

Expect more than half the country to vote for the Socialists and the PP, taken together. The failure of the largest two parties that sit in the centre of the spectrum to contemplate cutting a deal with the other is a tragedy for Spain. Why the need to bring extremists with a tiny slice of the total vote into power? Why not try and find a way of putting social liberalism and economic liberalism back together again? What is wrong with supporting both diversity in the social realm and an economic system based on value creation?

I think that the best way to see this election will be as an exercise in lion taming. Sánchez will try to convince voters that he was able to tame UP in coalition and bring ERC and Bildu closer to mainstream position. Expect Sánchez to attack Vox vigorously and hype up the PP’s vulnerability to some of the crazier views of the leaders of the smaller party.

Meanwhile, Feijóo’s side will try and sell the idea that Sánchez’s populist-adjacent politics are an existential threat to liberal democracy, while underplaying the risks of giving Vox a taste of power. The PP will also hype up the perceived seediness of Sánchez’s dealmaking over the last five years.

The PP has been cutting deals with Vox in areas where it failed to gain a majority following municipal and regional elections on 28 May, to well-deserved anger from many voters. It has established some red lines, like refusing to include a Vox politician who had previously been convicted of domestic abuse in a local deal in Valencia. Even so, deals between the PP and Vox will be Sánchez’s best card in a weak hand.

To cut a long story short, moderates, centrists and floating voters will have the unenviable task of deciding which is worse: paid-up communists, coup-mongers and terrorist apologists on one side or hard-eyed reactionaries, racists and bigots on the other. It is an unappealing choice.

Moribund liberal party Citizens (Cs) has declined to present candidates, so liberal voters will have to pick one side (probably Feijóo in most cases), hold their noses and hope that the winner either gets a majority or comes close to a majority. One advantage of a PP victory in this view is that the PSOE can rebuild in opposition under a new leadership, which will hopefully become more thoughtful about doing deals with populists.

Feijóo’s hold on the liberal centre ground will help him going into the election. I strongly suspect the right might win this time around, given the widespread rejection of Catalan separatism and Basque terrorism outside Catalonia and the Basque Country; as well as anger at Sánchez’s dealmaking; not to mention all the strong emotions generated by letting rapists out of prison early. Many will conclude that Bildu is worse than Vox.

The strong emotions cloud the fact that Sánchez has become the first Socialist PM to get Spain out of a recession in the modern era and delivered a perfectly respectable startup law, only to undermine it with a misguided reform of self-employment laws. Sadly for the incumbent PM, it is much harder to sell the idea that the hard right is fascistic if your own allies have supported a coup in the name of ethno-nationalism or made apologies for ethnic murder.

If the right is able to form a government, you can bet on tour-bus commentators droning on about the Spanish civil war in the 1930s without ever mentioning exactly why Sánchez is quite so unpopular with so many ordinary voters in the 2020s. Of course, terrorists, rapists and Catalan coup-mongers are much fresher in voters’ minds than former dictator Francisco Franco, who died in 1975 and was disinterred on Sánchez’s orders in 2019 to widespread indifference. Sánchez was just three when the dictator died, while Feijóo was 14.

Meanwhile, Spain has been a democracy for 45 years and these will be the 15th general elections since the adoption of the Spanish Constitution in 1978. Basque terrorists were active during the first 33 years of the revived democracy.

If Sánchez loses in July, disgust at his willingness to do deals with coup-mongers and former terrorists will be the real take-home lesson from his five years in power, along with fierce popular anger at the badly drafted consent law. Disgust is a powerful emotion. Elected officials should do everything they can to avoid provoking visceral reactions to their policies among moderate voters. Sánchez has failed to read the mood in the country multiple times over the last five years, although he can be fairly sure of maintaining the votes of die-hard Socialist voters. He might also pick up some votes to his left.

Hypocrisy is also likely to be a theme. Many voters will have vivid memories of Sánchez saying he wouldn’t sleep at night with Iglesias in the government in September 2019. The two politicians cut a formal coalition deal in January 2020, which gave Iglesias the role of deputy PM. The populist politician eventually left the government in 2021 on a quixotic mission to stop Isabel Díaz Ayuso of the PP from winning the regional elections in Madrid. He failed miserably after misreading her bare-knuckle politics as fascism. Instead, she combines economic liberalism with openness to Latin American immigration and capital, along with an abrasive and moderately populist edge that emphasises the many failures of communism.

Sánchez also regularly promised never to do a deal with Bildu from 2015, but quietly dropped this line when the radical Basque separatist party decided to support his no-confidence vote in 2018. The Basque party also abstained in the vote to make him PM in 2020, as did ERC, getting the Socialist/UP coalition over the line in a tight vote. Both parties supported Sánchez’s budgets for 2021, 2022 and 2023 following backroom deals to bring government investment to their territories.

The memories of the broken promises and pork-barrel politics are fresh in the minds of many voters outside the Basque Country and Catalonia. Bildu and ERC together got less than 5% of the total Spanish vote in November 2019 and are wildly unpopular with many voters in Spain’s other 15 autonomous communities. The only possible exception is Navarra, which lies next to the Basque Country. Bildu received 17% in the recent regional elections there, thanks to a section of the population that identifies as Basque.

If Sánchez loses in July, future historians will probably pin 9 May 2023 as the key date in his downfall. On that day, an organization that represents the victims of Basque terrorism announced that 44 of Bildu’s candidates for the upcoming municipal and regional elections had terrorism convictions, including seven with blood on their hands. It was a shocking moment for the Socialists, whose leaders had previously tried to present Bildu as a mainstream left-wing partner. The Socialists did worse than expected in the subsequent municipal and regional elections; and Sánchez called a snap general election soon afterwards.

The wild card is what will happen in Catalonia if Feijóo does a deal with Abascal after the election. One of Sánchez’s biggest successes has been in undercutting separatist narratives. A PP/Vox deal would be a gift to ERC and other separatist parties, who often spin yarns about the alleged ethnic superiority of native Catalans over their neighbours in the rest of Spain and migrants from other parts of the country. A right-wing PM in Madrid struggling to contain the atavistic, reactionary and fascistic tendencies of his allies means these narratives might once again gain some traction in Barcelona.

For some reason, most populists rarely do any reading on populism (Iglesias is an exception). This lack of self-awareness makes populists very annoying on the internet. If you find this column outrageous, please use the energy you would have spent arguing with me elsewhere. I recommend reading the book below instead. The comments are closed. See you next week!

Further Reading

What Is Populism? by Jan-Werner Müller

Sharpen Your Axe is a project to develop a community who want to think critically about the media, conspiracy theories and current affairs without getting conned by gurus selling fringe views. Please subscribe to get this content in your inbox every week. Shares on social media are appreciated!

If this is the first post you have seen, I recommend starting with the second anniversary post. You can also find an ultra-cheap Kindle book here. If you want to read the book on your phone, tablet or computer, you can download the Kindle software for Android, Apple or Windows for free.

Opinions expressed on Substack, Twitter, Mastodon and Post are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.