Unfulfilled Promises

The end of Spain's long boom more than a decade ago led to the ideal conditions for populism to thrive

"El Movimiento del 15 M ' Los Indignados de San Telmo ' Las Palmas de Gran Canaria" by El Coleccionista de Instantes is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

If you want to understand Spanish politics on the eve of the next general election, you need to go back to 15 May 2011 when there were a series of anti-austerity demonstrations across the country. Social groups like Youth Without a Future (Juventud Sin Futuro) had organised the protests beforehand on social media. Some 50,000 people showed up at one demonstration in Madrid alone. The movement slowly grew over the next couple of years, with many more demos. Occupations of public squares in various cities became very newsworthy.

The backstory was Spain’s long boom. It began in earnest during the so-called Spanish miracle (1959 to 1974), when Barcelona, the Basque Country and the shipyards of Galicia began to industrialise in a very serious way during the final years of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship but before the international oil crisis. At the same time, the country became a superpower in tourism, particularly along the Mediterranean coast.

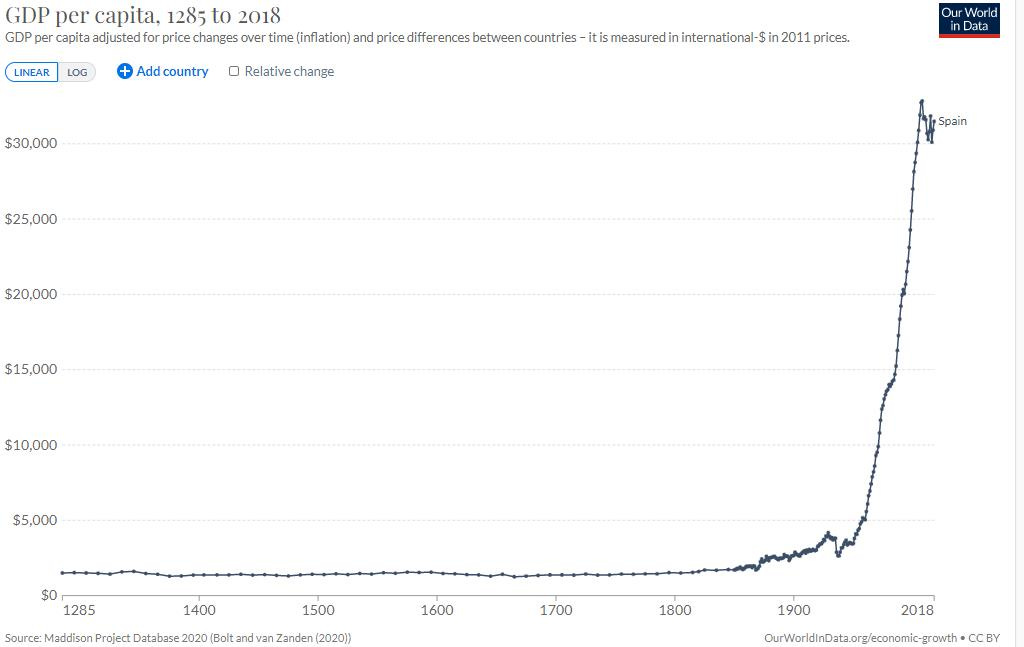

Spanish GDP per capita went from $2,750 in 1974 (at the end of the miracle years) to $4,356 in 1978 (when the vast majority of the electorate voted for the current Constitution) and $4,700 in 1985 (when Spain joined the EU). It soared to $17,107 in 2002 (when Spain replaced pesetas with the euro) and hit a peak $35,511 in 2008.

We all know what happened around this time. A credit crunch began in 2007 in the US and the UK and accelerated in 2008. Bear Stearns fell in March 2008, followed by Lehman Brothers in September 2008. Spain’s former Socialist Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero famously refused to say the word “crisis” (which means both “crisis” and “recession” in Spanish) for many months, which meant the government was unprepared when the long boom finally ended. Spain officially entered a fierce recession early in 2009.

The latter years of the boom had been driven by cheap debt. The peseta carried high interest rates, while rates were much lower for the euro. Credit became ultra-cheap during the transition between the peseta and the euro, leading to a debt-fuelled housing bubble. Property prices rose 200% between 1996 and 2007, with home ownership above 80%. Some banks were offering 50-year mortgages before the crash.

When the recession hit, Spain’s previously buoyant construction industry fell off a cliff and house prices collapsed. Some 4m people were unemployed in 2009. The numbers continued to rise as the recession took hold, getting close to 6m in 2012. The total population in the same year was just over 47m (including 8m children), which means more than 15% of adults were on the dole. GDP per capita fell back to $25,754 by 2015. Nearly a quarter of a million homes were seized by banks due to non-payment of mortgages between 2007 and 2010.

By Max Roser - Our World in Data, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=115232379

There was a “lost generation” of young people, many of whom became enthusiastic supporters of the 15-M movement. The press dubbed them “los indignados” or “the indignant ones.” The name is telling. Iñigo Errejón, a young political science lecturer who studied the movement and then became a populist-left politician who tried to shape it, often says that the movement had a “conservative” edge. In one interview, he said it was “more regenerative than revolutionary.” He also says: “Rather, it confronted the existing political regime with what it had itself promised.”

Let’s take a second to stop and reflect on this point. What, exactly, had been promised? People who had grown up in the boom years had expected that they would be able to find a job, buy a flat and raise a family. They thought that they would be able to earn more than parents. They thought that getting a degree or a vocational qualification would be a golden ticket.

Instead, the crash undercut all the implicit promises of the boom years. The first people in their families to graduate from university often found themselves on the dole and priced out of the property market. Theft from supermarkets boomed as people struggled to survive. Many lived in the spare rooms of relatives, with very little cash to spare, while many others emigrated in search of a better life to cities like Berlin and pre-Brexit London. Settling down in Spain and starting a family seemed like an impossible dream for many members of this generation during the worst of the recession.

The anger of the indignant ones was obviously well deserved. Unfortunately, anger is bad for analytical intelligence and populists love offering black-and-white solutions to complex problems. One of the groups that organized the 15-M movement was called Real Democracy NOW (Democracia Real YA). It proposed a populist critique of the institutions of liberal democracy. Narratives about the illegitimacy of actually existing institutions were helped by breaking news stories about widespread corruption from mainstream politicians from across the political spectrum during the boom years.

Errejón and a one-time friend of his called Pablo Iglesias formed a populist-left party called We Can (Podemos) in 2014 (it later changed its name to Unidos Podemos and then Unidas Podemos, or UP; and Errejón formed a smaller breakaway party in 2019). They worked hard to overcome the “conservative” elements of the 15-M movement. At the same time, they modelled their party on the advice of Ernesto Laclau, an Argentine thinker who proposed Latin American populism as a way of dealing with the many failures of Marxism. Podemos hit an absolute high of 5.2m votes in the 2015 election and a relative high of 21% in 2016 (as Unidos Podemos), as we noted on 17 June.

Populism spread like a virus through Spanish politics during the worst years of the recession. In June 2011, more than 2,000 indignant ones circled Catalonia’s regional parliament. Establishment nationalists had to escape by helicopter. Artur Mas, a Catalan nationalist who had been first minister of the region since December 2010, cynically decided to harness the power of populist anger to reinforce his own position, despite leading a party with a disgraceful track record on corruption. He designed a populist independence movement, which divided Catalonia in half before the failure of its coup attempt in 2017.

A party called Citizens (Ciudadanos) was born in Barcelona in 2006, just before the end of the boom. It positioned itself as a liberal party from about 2014, with a fierce criticism of populism and nationalism in Barcelona and elsewhere. However, there are dangers in this approach, as we have mentioned here and here. The party eventually collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions. Meanwhile, a hard-right / far-right party called Vox was founded in 2013, with a mission of combating populism. Perhaps inevitably, it has also become a populist party.

Eventually, of course, the Spanish economy got back on track, thanks largely to reforms led by Luis de Guindos, a former investment banker with Lehman Brothers, who had also worked at the finance division of Pricewaterhouse Coopers and taught finance at a leading business school. He was appointed Minister of Economy and Competitiveness by conservative Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy in December 2011 shortly after the centre-right Popular Party (PP) beat Zapatero’s Socialists. The former banker did the job for nearly seven years, taking on the industry brief as well halfway through his time as a minister. During this time, he set up a “bad bank” to handle foreclosed property in the hands of the banking sector and negotiated a bailout for Spain’s beleagured banks of up to €100bn from the EU in June 2012.

Shortly after the bailout, Mario Draghi, then president of the European Central Bank (ECB), gave a famous speech saying that the institution would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro. This is often considered the turning point in the great recession in Europe. Investment slowly began to flow again throughout the eurozone, creating the conditions for economic growth and job creation. De Guindos eventually joined Draghi as vice-president of the ECB in 2018. He still holds the post, while Draghi became a technocratic Prime Minister of Italy in 2021 and 2022.

"Governing Council Press Conference - 13 December 2018" by European Central Bank is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

De Guindos on the left and Draghi on the right in 2018

Outside financial circles, de Guindos and Draghi rarely receive the credit they deserve for getting the Spanish economy back on track. Populist critiques go straight for our emotions, while reformist politics aimed at creating investment-friendly conditions can be difficult to understand, particularly for people who have had little exposure to economics. It is hard to turn sound economic stewardship into a soundbite ahead of an election.

Thanks to the consequences of de Guindos and Draghi’s interventions, though, international investors returned to Spain. As a result, the economy started to grow again and many former indignant ones were finally able to find jobs, buy homes and maybe have a kid or two (although the number of kids per woman has continued to fall from 1.44 in 2008 to a new low of 1.19 in 2021).

As the economy recovered, UP’s share of the vote fell to just over 3m (around 13%) by the time of the last general election in November 2019. It has since joined a new hard left movement called Addition (Sumar), which is polling around 12% ahead of the upcoming election.

There were still 2.7m unemployed people in Spain in May. While this is obviously a lot, much of it is concentrated in Andalucia and Extremadura in the south of Spain, as well as the two autonomous cities in North Africa, the Canary Islands and rural areas further north and east. As many young people in large cities have found jobs, GDP per capita started to rise again, getting back up to $30,104 in 2021.

Of course, we live in an imperfect world. Many of the jobs that were created after the boom were unstable and badly paid, as well as often being based on temporary contracts. However, many young people were able to use these temporary contracts to get their lives back on track after a few truly depressing years. Their first jobs after the crash might not quite live up to what they thought they were promised during the boom years, but a temporary contract is certainly better than living in the spare room of a relative and stealing food from the local supermarket.

While populism is still alive in Spain, the conditions for it to thrive are no longer quite so good as they were a decade ago*. This is a good thing! Your education and your career are meant to be more interesting than your politics. The same is true of your social life, your love life, making a home, raising a family and maybe taking a hobby or two seriously. In a healthy society, politics is meant to be boring.

The 2023 general election is likely to be a turning point between exciting but toxic populism and boring old administrative politics. As we have mentioned before, the vote is a straight fight between the centre-left and the centre-right, with plenty of attention on which populists are likely to be the junior partner in a post-election coalition deal.

Sadly, nobody has found a way of avoiding recessions in a capitalist economy, which ebbs and flows in ways even economists find hard to predict. We don’t know when the next one will come or under what circumstances, but we can be sure that there will be another one at some point in the not-too-distant future, with the risk of another wave of populism in its wake. What can you as an individual do to prepare for the next recession?

One of the key lessons of Spain’s Great Recession is that excessive debt is dangerous when the economy is shrinking. It pays to be very conservative when you work out the budget to buy your first home. You should also try to pay down the mortgage as fast as humanly possible and be reluctant to upgrade to a bigger home. Paying off your credit card in full every month and avoiding loans for consumer items are both pieces of advice that have stood the test of time.

Also, try and put a little money aside every month in the good times. Invest sensibly over the long term and avoid get-rich-quick schemes. Working for a startup is a great choice when times are good, but safety should be a priority in a recession, when well-established companies have an advantage. Whether you work for a startup or an established company, creating value for others is always going to be a defensible position. Be aware of the balance sheet of the company where you work. Companies with lots of debt are worse bets in a recession than those with healthy cashflows and modest debt.

Also, in an exponential world, your skills can get past their sell-by-date very fast. Lifelong learning is more essential than ever in order to cope with whatever curve-balls the economy might throw at us in the future. An economist once told me that Zapatero should have rushed to retrain as many construction workers as possible in 2008 as soon as it became clear that the economic cycle was going to change. The same advice applies to individuals too. We all need to keep our skills up-to-date.

Finally, think twice before voting for populist parties with wild plans to change everything at once. You might not get the result you wanted! As floating voters, we should also seek to punish politicians who mismanage the economy, whether that is Zapatero on the Spanish left or Liz Truss on the British right.

As usual, whenever we discuss populism, the comments are closed. Life is too short to spend it arguing with populists who have never read a single book on populism. They tend to be unreflective and quick to deploy conspiracy theories to protect their simplistic worldview from contact with the complexities of real life.

If you support populists like UP, Vox or the Catalan separatist movement, please gain a little self-awareness by reading about populism and the conditions that make populism seem attractive instead of arguing with people like me on the internet. See you next week!

*The populist right does have the wind at its back across Europe, but the polls show Vox languishing below 15% at the moment, so let’s not get too over-excited. That is likely to be less than a quarter of the combined vote for the Socialists and the PP.

Further Reading

The True Believer by Eric Hoffer

Sharpen Your Axe is a project to develop a community who want to think critically about the media, conspiracy theories and current affairs without getting conned by gurus selling fringe views. Please subscribe to get this content in your inbox every week. Shares on social media are appreciated!

If this is the first post you have seen, I recommend starting with the second anniversary post. You can also find an ultra-cheap Kindle book here. If you want to read the book on your phone, tablet or computer, you can download the Kindle software for Android, Apple or Windows for free.

Opinions expressed on Substack, Twitter, Mastodon and Post are those of Rupert Cocke as an individual and do not reflect the opinions or views of the organization where he works or its subsidiaries.